Rotunda

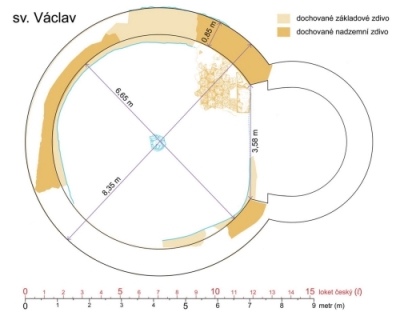

The word rotunda designates a type of early medieval ecclesiastical buildings. In fact, it is a Romanesque church with a circular nave and an almost semi-circular apse, where an altar was usually placed. It is a simple construction with very few architectural elements. Although they are all very similar, no two rotundas are identical. These structures are not very widespread and in their time they were built only occasionally. In the 9th century rotundas were erected on the territory of Great Moravia, and were uncovered during archaeological research in Mikulčice, the Old Town near Uherské Hradiště and also in Znojmo. The oldest rotunda in Bohemia is a church in Budeč dating back to the 10th century, which can be admired in its full glory even today. The youngest rotundas in the Bohemian and Moravian regions are most probably from the late 12th century. There are currently 49 rotundas registered in these areas. St. Wenceslas Rotunda discovered at Prague’s Lesser Town Square bears the number 16 and is dated to the early 11th century.

History of the Rotunda

In the words of legends

When prince Wenceslas was assassinated in Stará Boleslav, most probably in 935, he was not yet known as Saint Wenceslas. At the time, canonisation required evidence of miracles after death as well as translation of relics. The location of St. Wenceslas Rotunda at the Lesser Town Square in Prague is directly linked with both the translation (the transportation of the saint’s body) to St. Vitus Cathedral at Prague Castle in 938, and a number of miracles that occurred after Wenceslas’ death.

The Wenceslavian legend Ut annuncietur I, dating back to the early 13th century, mentions a place where a miracle associated with St. Wenceslas is said to have taken place in the 10th century. Allegedly, an act of divine intervention occurred by which the prisoners were freed from their shackles and led out of the prison at the exact same moment when a procession accompanying the carriage with the murdered St. Wenceslas was passing it – “in commemoration of this miracle, a church was built in honor of the beatified martyr at the place where the prison once stood, and which stands here to this day.” The mention of the church erected at the place where the miracle had occurred is related to the local St. Wencleslas Rotunda, and is the first written indication of its existence. The Rotunda itself was not built until approximately 150 years after the transfer of the prince’s body and the completion of the legend called Ut annuncietur I.

A stone circle formed of flat marlstone slabs dating back to the times of the translation was discovered under layers of soil (Discovery). The seemingly small diameter of the stone circle suggests the first Christian structure located at this place, which would also be the oldest church outside Prague Castle.

As time passed by

The rotunda was most likely built as a great parish church serving the core of the original city of Prague. With the passing of time, however, it ceased to fulfill its ecclesiastical purposes. St. Nicholas Church then took up the function of the parish church for the new, early-Gothic city founded by Ottokar II of Bohemia in 1257. At that time, embossed ceramic tiling inside the rotunda was replaced with marlstone blocks. However, part of the original flooring had collapsed leading the stonemasons at the time to merely level this section up and cover it with new marlstone tiles. Without their knowing they have therefore preserved a piece of heritage that was only discovered some 750 years later.

The rotunda is first mentioned in the archival documents of 1309, where it appears as a little suburbium church managed by Priest Henrik. It is referred to as a chapel with a graveyard adjacent to the parish church of St. Nicholas. It is likely that in the 14th century a new entrance from the western side was created, leading from the upper part of today’s Lesser Town Square. The rotunda was accessible by stairs and was also being used as a burial place. Archaeological research on site revealed that a knight and his family were interred here (See “findings” section.).

Fires in the years of 1420 and 1541 limited the ecclesiastical use of the rotunda. It should be remembered that at the time, the rotunda was already part of St. Wenceslas Church. After the second fire, it served merely as a garbage dump and became a rubble site. Only in 1599 was it finally renovated: new tiling was laid down and it was also newly plastered. But gradually the importance of the rotunda began to falter again. Reportedly, in 1612 several Lesser-Town townspeople complained about “dirt and stench in the vicinity” and called upon the municipality to take better care of the memorable little church.

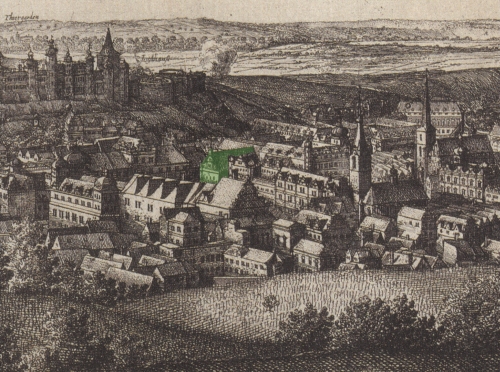

The appearance of the rotunda at the time of Rudolph II is also documented by period iconographic sources. These attest to the fact that, even 550 years after its construction, the rotunda still retained its Romanesque character. Its appearance was captured by Roelandt Savery, the court painter of emperors Rudolph II and Matthias.

After the Battle of White Mountain the parish Church of St. Nicholas was passed to the Jesuit order. The church with the attached rotunda was to become the new parish church, for the purposes of which it had to be extended. Between the years of 1628 and 1632 a separate sacral building was erected. Its western façade with a gable and a roof is depicted in Václav Hollar’s panorama of Prague.

During the subsequent construction of the Jesuit House of the Professed (the administrative headquarters of the order for the whole province of Bohemia), the current seat of the Faculty of Mathematics and Physics, Charles University, the structural stability of the eastern part of the older Baroque church containing the rotunda was significantly damaged. The 1730s church was therefore demolished in order to make the best possible use of the space during the 1684-1688 construction work. The demise of the order in 1783 resulted not only in the nationalisation of the church, but also in further formal alterations. A year later, the crypts were backfilled and the so-called “Land tables” (Desky zemské) were placed in the former church.

The building of the former Professed House remained unchanged in the course of the following centuries. It is nevertheless possible that the First Republic constructors could have encountered some of the remains of the old church.

A new beginning?

Only when the Professed House came to be reconstructed by the present-day Faculty of Mathematics and Physics, the backfilled space initially identified as an underground sacristy belonging to the Baroque church was cleared out. The importance of some of the findings became apparent only after a more thorough examination of the backfilled, plastered space (later identified as crypts) and the discovery of the circular masonry of the rotunda that followed.

In the 1930s, construction workers destroyed the foundations of the Rotunda’s apse when building sanitary facilities for the employers of the Czechoslovak National Bank housed in the Professed House during the era of the First Republic. Its destruction was not purposeful, the builders merely failed to recognise it.